When Alana Evans became the Vice President of the Adult Performance Artists Guild (APAG) in 2016, she didn’t expect that convincing the adult entertainment industry of her right to unionize would be such a formidable task. But getting everyone around her, industry-folk and public alike, comfortable with the idea of a union of entertainment sex workers has been her biggest challenge since APAG was federally recognized nine years ago.

Entertainment sex work is a highly profitable market, contributing billions of dollars to the U.S. economy each year. Just the porn and strip club markets in America generate approximately $15 and $7.7 billion dollars per year respectively, yet its workers are constantly battling pervasive cultural stigma and workplaces that rarely see them as the professionals that they are.

As a result, these sex workers face widespread discrimination, harassment, and wage theft, without the security of labor protections that employees in more conventionally acceptable industries have come to expect. Unionization allows entertainment sex workers to offset this asymmetry in power by proactively bargaining for fairer working conditions and establishing a formal grievance process that their employers must comply with under federal labor law. But the process itself is laden with barriers that are exacerbated by the contentiousness of their work.

APAG is an adult entertainment union with over 1400 members encompassing sex workers across the adult entertainment industry, including porn performers, content creators, phone sex operators, webcam performers, and more. Evans was elected to the role of President of the union in 2018 and describes the recurring debate around sex work as legitimate labor as one of the most significant hurdles that APAG has had to overcome. Setting up, joining, or being active in a union requires a general consensus that sex workers should be afforded the same right to engage in collective bargaining as any other employee in America. And while most sex workers tend to be in agreement about this, the public is yet to catch up.

“Obviously, the biggest challenge has been acceptance within an industry that is not inherently used to organizing. We had to work really hard, even within our own industry, to prove to our community, regardless of the work that we were doing, that we were here for the right reasons. It was an uphill battle,” Evans said.

The perception of sex work as morally deviant or exploitative has long been used as a tool to delegitimize sex workers and weaponize public policy against them through policing and anti-sex work legislation. This has meant that sex workers who attempt to unionize are also burdened with the task of justifying their labor, which in itself can be an exhausting and disincentivizing task.

Demonstrators chant in support of decriminalizing sex work during a rally held in Las Vegas on June 2, 2019. Photo from the Associated Press.

Gregor Gall, a professor of industrial relations and research associate at the University of Glasgow, has published several papers and books exploring the fraught landscape of sex worker unionization across the world. According to Gall, exacerbating the issue of a lack of productive discourse around sex work is the growing number of workers in the industry and the relatively limited number of activists available to organize them.

Internet based sex work through phone sex, camming, or platforms like OnlyFans has democratized access to sex work, increasing the number of workers in the industry. Yet several of these workers are transient. Jo Weldon, a sex worker, activist, author, educator, and current Headmistress of the New York School of Burlesque describes how because of changing laws affecting adult entertainment, unsafe workplaces, or financial circumstances, many sex workers frequently change where they are employed, sporadically engage in sex work based on economic need, or change professions within the industry itself.

“People dip in and out. Most people don't consider it a career … And so a lot of people who are sex work activists really identify with the work [whereas other] people are like, ‘Ah, yeah, I'm a stripper, but I identify much more with my other job, or my family or my community than I do with sex work,’” Weldon said.

This ever-evolving nature of sex workers’ labor can stifle unionization efforts, which often require dedicated effort over long periods of time within the same workplace or community of interest. The consequence of this is that sex worker organizing tends to rely on a small group of hyper-activists who bear the brunt of organizing and petitioning for a union, and then once it is gained, meeting members’ various needs.

This can be fatiguing, lead to eventual burnout, and have a demoralizing effect on organizers, predisposing sex worker unions to fragility. “It's emotionally draining,” said Evans. “That was the hardest adjustment for me to make, was having to be the person that so many would come to when people were suicidal in the industry … On many nights I would be up until the middle of the night, you know, helping people through crises and things like that.”

Beyond these internal challenges to effective unionization, sex workers also have to contend with retaliatory tactics from management at strip clubs and porn production companies, who are opposed to the formation of a union. According to Weldon, entertainment sex workers are “constantly negotiating with the clubs for your right as a laborer and with the government for your right to the job.”

The trajectory of the Exotic Dancers Alliance (EDA) perfectly exemplifies this tension. The EDA was founded in San Francisco in 1993 in response to unfair working conditions and a lack of a collective voice for the dancers. In the process of attempting to establish their union, EDA’s two main activists were essentially fired when they showed up to work as they were continually told that shifts were full and that the club did not need any more dancers. Around the same time, in 1995 dancers at another club were fired after they joined the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), and in 1997 a third club was shut down after its workers attempted to unionize through SEIU.

Strippers at the Star Garden Strip Club, the only unionized strip club in the country. Photo from Teen Vogue.

Similar tactics from employers continue to persist even today. In 2022, three dancers at Star Garden Topless Dive Bar, a strip club in North Hollywood, were fired after bringing their concerns to management. 15 more were locked out, being told by security guards at the club that they were on a list of people not to be let in after they presented a petition to management demanding “better protection from the club and rules for customers around things like filming dancers and egregious drunkenness.”

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the federal agency that enforces the right of private sector employees to unionize in the U.S., even filed a complaint in support of the dancers, with an NLRB spokesperson telling the Los Angeles Times, “The Star Garden dancers concertedly raised concerns about their health and safety, and the employer unlawfully retaliated against them because they did so.”

Evans’ predecessor at APAG also faced pressure from his employers to take a step back from union activity. “Our first president wasn't very active because he was being blackballed, if you will, and it was affecting his work as an honest performer. He'd show up (to work) and have people give him a hard time, kind of harass him about stuff,” she said. Eventually, frustrated APAG members asked him to make a choice between union organizing or continuing his professional work. According to Evans, “That was the fastest decision he ever made. He was, like, ‘Yep, it's yours.’” After his resignation, Evans won an uncontested election to replace him as President.

Gall also describes how employers subject workers to changing rules and regulations in an attempt to undermine the concerted activity of workers to unionize. “In most cases, in the United States, what those employers are doing is lawful. It's not an unfair labor practice. And if it was, you'd have to take them to court again and prove in a court of law that it was an unfair labor practice, which is not an easy thing to do. You need lawyers, you need time, you need money,” he said. These conditions mean that sex worker unions start up in a wave of enthusiasm and eventually get ground down by the amount of work involved and the lack of success that they see.

.jpeg)

Strippers at the Star Garden Strip Club, the only unionized strip club in the country. Photo by Alyson Aliano, NPR.

According to Gall, this issue is compounded by the fact that sex workers’ attempts to organize are rarely supported by mainstream labor unions. Collaborating with traditional unions with experience organizing various workplaces can present a vital benefit to workers. Institutional support in the form of organizer staffing, finances, and legal guidance can provide important leverage when negotiating with employers, and give clearer direction to organizing efforts.

But when it comes to organizing sex workers, more sizable unions like SEIU have waited for sex workers to approach them rather than initiating the union organizing themselves, Gall said. Any support these unions provide is generally only commensurate with sex workers’ existing efforts, not their growth or expansion into new areas.

Mainstream unions also consist of local chapters which represent a diverse range of employees. SEIU alone is composed of a variety of service industry professionals across its locals, including hospital and home care workers, government employees, janitors, security officers, and others, which can present competing interests for sex workers who are trying to unionize.

These unions also impose dues, where union membership fees are collected from members, sent to a national chapter, and then disbursed to locals based on pre-drawn budgets. Conventional dues structures can impose an additional financial burden on entertainment sex workers who, in some cases, are already subject to some form of wage theft from their employers, like having to pay stage fees to dance at a club.

APAG’s organizing efforts originally began under the umbrella of a parent union — the International Entertainment Adult Union (IEAU), which organizes the “Adult Film Industry, Web Cammers, Exotic Dancers, EDM Dancers, Bartenders, Cocktail Waitresses, UFC Fighters, Boxers, Security Guards, DJs and more.”

But this relationship turned fraught when APAG organizers began to feel that IEAU no longer represented their needs. “It got to a point where it became very clear that at no time was our mother union ever going to have our best interest at heart,” Evans said, “At that point, we started to separate from them, and that was the best decision we had made.”

According to Evans, dues that APAG members paid to IEAU were not being returned to the union to support their organizing efforts. Separating from their parent union meant that APAG could refuse to charge member fees in their early stages. Prioritizing the organizing work over collecting fees, Evans has funded a majority of APAG’s needs herself, with plans to potentially start taking dues this year. “We wanted our workers to know that we were here to do the job and not here to make money, which is more what our mother union looked like,” she said.

APAG eventually won a lawsuit against IEAU, which mandated that the parent union turn over the trademark to the APAG name and agree not to organize in any other part of the industry except for dancers. “At that point, we were really happy. No more shackles and chains … The day-to-day work of it really had evolved into all of this battle over just the founding structure of our organization, to now we get to just do the work,” Evans said.

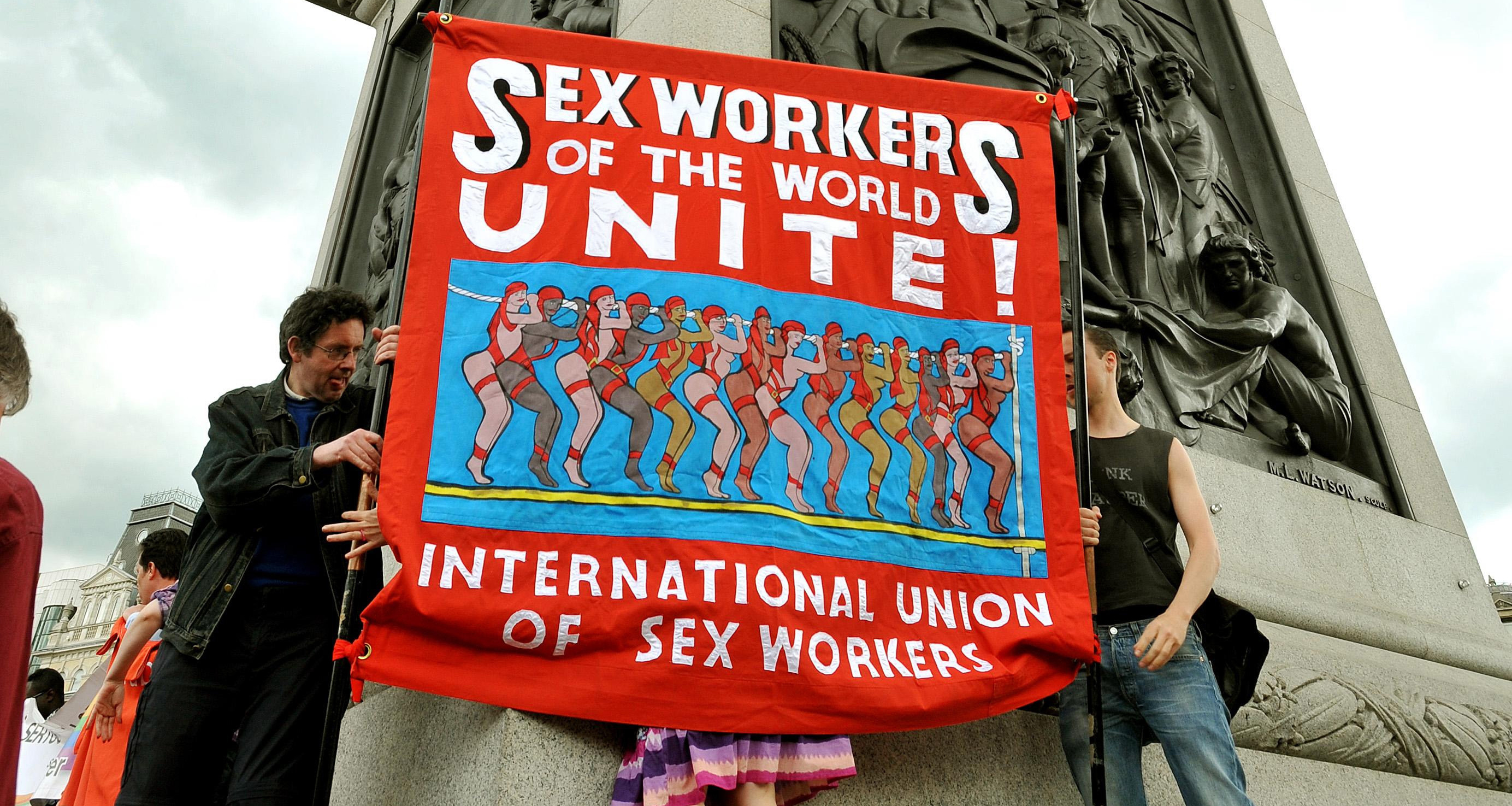

International Union of Sex Workers banner at a May Day rally at Trafalgar Square on May 1, 2010. Photo from the Morning Star (UK).

All these barriers coalesce to produce a daunting environment in which sex worker unions are formed. But it is not impossible. APAG is currently the only federally recognized union for porn performers (even though its membership is much broader) and has taken on a range of advocacy work at the national level.

The union has campaigned against banking discrimination in Washington D.C., negotiated with companies like Meta and Instagram to fight the deplatforming of its members, expressed solidarity with other unions through direct action, and built coalitions across industries to bolster their own organizing efforts. “We've gotten ourselves into a lot of rooms where no one would have expected us to have a seat at the table,” Evans said.

While still in nascent stages overall, other adult entertainment workplaces like strip clubs, are also unionized across the country. In 2023, workers at Star Garden in Los Angeles became the first unionized strippers in the U.S., represented by the Actors' Equity Association (AEA). Later in the same year, strippers at Magic Tavern in Portland, Oregon, also unionized with AEA.

Even in the face of the Trump administration’s anti-labor policies that have made unionization across industries a risky endeavor, sex worker activists have continued to forge a path forward to building negotiating power in their workplaces. In the shadow economy that is sexual labor, the connections and support networks that sex workers have been able to form through their organizing are critical in allowing them to feel a sense of community that is free of judgement. And as generations of sex worker activists turn over, the legacy of their work leaves behind an environment that is slightly more conducive to the next wave of union organizers.

According to Weldon, young sex worker activists today are doing things that she never could have dreamed of even in the heyday of her own organizing efforts. “Now, a lot of people in activist spaces believe in the benefit of experience rather than the bias of experience, and I think that there are a lot of sex worker activists with both professional experience in the sex industry and professional experience as legislators, lobbyers and media analysts,” she said. “The coalitions that are formed among young activists are…they're the most powerful I've ever seen. They've been a huge presence. I hope that they love each other and are kind to each other, because I'm still friends with the same activists I was friends with 35 years ago.”

Ultimately, sex worker activists throughout generations have been united in their efforts to achieve the same goals as workers in many other industries. Yet the myriad of challenges they face as a result of the stigma around their professions has left them lagging behind other workers in the fight to build safer and more equitable workplaces. But it is their determination to sustain a collective sense of labor solidarity that drives organizing efforts even today.

“There's a base level sense of shared passion for the cause. And the cause is freedom, you know. Social mobility, financial security, physical safety. Those are the goals,” Weldon said, “I don’t give a fuck if people respect me, but they have to respect my rights. I don't care about respectability, but I care about my access to the same things that everybody else uses to get by.”